By Michael Kinney

Michael Kinney Media

On the evening of April 3rd, my cell phone rang with a number I didn’t recognize. Normally, when that happens, I usually don’t answer it because of telemarketers. But in these days of social isolation, you sometimes welcome any type of conversation.

So, I answered it.

But it wasn’t a telemarketer, a friend or anyone I had ever talked to before. It was a doctor from St. Anthony Hospital in Oklahoma City on the other line.

He was confirming what I had pretty much figured but wasn’t positive on. He got right to the point and told me I had tested positive for the coronavirus.

By that time, it had been two days since I had gone to the emergency room with a rapid heartbeat, the shakes, fatigue and shortness of breath. Even though they told me then it would take a few days for the test results to come through, I had a pretty good idea that I had contracted the virus that had shut down most of the United States and a large part of the world.

As of April 10, more than 1.6 million people have contracted the coronavirus; that includes 102,000 deaths from it.

The United States has seen 502,318 cases of COVID-19 and 18,725 deaths. Oklahoma, which was last in the nation in testing, has 1,684 cases and 80 deaths.

However, by the time you read this paragraph, those numbers will have gone up considerably.

It’s hard to imagine that my true indoctrination in the effects of the coronavirus began a month ago.

It started as an unremarkable night during the long stretch of an NBA season.

But on March 11 when the Oklahoma City Thunder hosted the Utah Jazz, no one was really talking about the contest before the game tipped off. At that time the coronavirus had just really started to seep into conversations and media coverage.

However, when that night was over, it seemed everyone in the United States had some type of basic knowledge of what the coronavirus was and what it had been doing in other parts of the world.

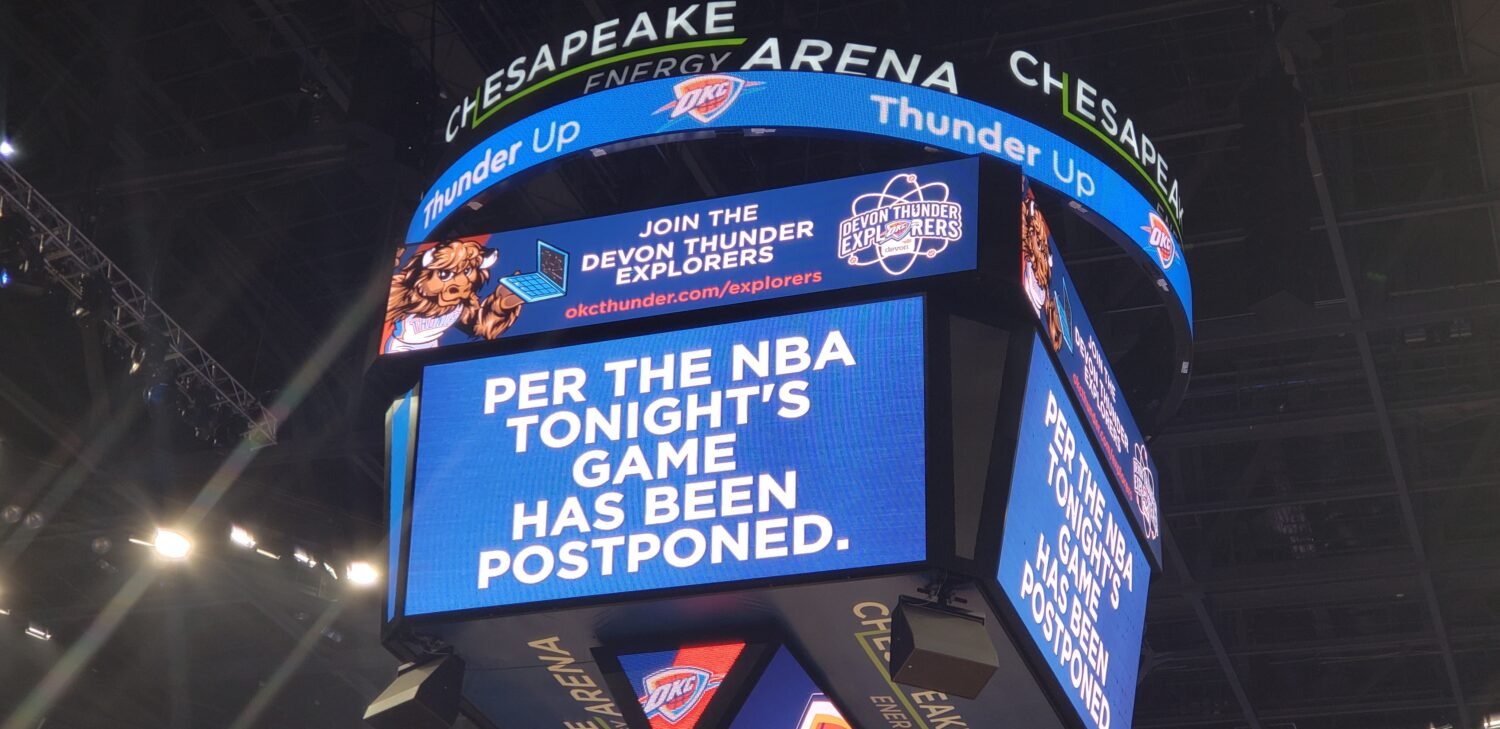

Right before the Jazz and Thunder tipped off, I was near the floor taking video and photos when the players were pulled off the court and taken back into the locker room without any explanation.

More than an hour later, the game was canceled after it became known that Utah center Rudy Gobert had tested positive for the coronavirus. It wasn’t given the designation of COVID-19 until later.

That one act set off a chain reaction. By the time I left the Chesapeake Energy Arena that night, the NBA had postponed its entire season. In the following days, other sports leagues had followed suit.

That was the alarm heard around the world. Since that moment, the United States and other countries have come to a standstill in many ways.

I had been in social isolation since March 20. Only going out to grocery stores and the pharmacy. Or to take a walk around my neighborhood for exercise.

Yet, on March 24, I had started feeling symptoms that could have also been associated with a cold. Things such as a scratchy throat and a tightness in my chest.

But it wasn’t until March 29 that I began to really feel its impact. It included head and chest pressure, a small cough and fatigue.

The entire time I was in contact with my doctor through emails. He told me since I didn’t have any problems breathing, the best thing I could do was just hunker down at home and ride it out.

That was the plan until the morning of April 1, when after a long night of dealing with symptoms, I woke and my heart was racing. Because I was in the process of writing a story on the impact of COVID-19 on those with underlying conditions, I felt I needed to go to the ER.

So, that is how on what is normally April Fool’s Day, I would find myself on a gurney at 5 a.m. with wires attached to me.

While all the tests came back normal, I was still given the COVID-19 test. At that point I had heard of it, but didn’t know exactly how it was performed. So when they said they needed to take a swab, I opened my mouth. The nurse said, ‘no, not that way.’

The swab actually went up my right nostril. I thought she hit brain matter. They then did the same on the left side. It was unpleasant and they said they would have the results in two or three days.

That was it. I was at the ER for just over an hour before leaving with a complimentary cotton face mask and what I assume will be an extremely high bill.

From that point, it was just a lot of praying and a waiting game until I got the results back April 3.

Not only did I get a call from the doctor at the hospital, but Elizabeth Billingsley, an RN with OKC-County Health Department, called a few minutes later to make sure I was taking the right precautions and isolating myself from the public for a time being.

According to both, once I have had no fever for three consecutive days and had been away from the public for at least seven days since the onset of the illness and once I was feeling better, they believed I would be clear of the virus.

I had achieved all of those benchmarks by the time I got the call from Billingsley on April 8. She checked on my status and asked a series of questions before telling me I was clear of COVID-19 and was no longer shedding the virus as well.

“As far as getting it again, you should be immune to it at this point,” Billingsley said. “Once it has passed out of your system, your body has made antibodies to it and you can’t get re-infected. At least that’s what they’re telling us at this point. They don’t know how long that lasts, but you’re immune to it at least in the short term.”

Immunity to the coronavirus is something that is being debated and looked into by scientists across the world. There is even talk of creating certificates of immunity if they are able to know for sure that people who have recovered from the virus now carry antibodies that will keep them from getting sick again.

“I mean, it’s one of those things that we talk about when we want to make sure that we know who the vulnerable people are and not,” Dr. Anthony Fauci, a member of the White House’s coronavirus task force, told CNN. “This is something that’s being discussed. I think it might actually have some merit, under certain circumstances.”

Even though I was told I will still have fatigue and have symptoms pop up for a week or two, this was all great and relieving news.

Compared to what others have had to deal with, what I went through was mild. I didn’t have any noticeable fever, if any at all. No congestion and no problems breathing during the entire ordeal.

“You were a relatively healthy person,” Billingsley said. “You kind of got it and kicked it and moved on. But some of the people I talked to aren’t so healthy. So it’s not that easy.”

What got to me the most was the anxiety and fear at times. That is why I waited until I got the all-clear before writing this column or informing anyone outside my immediate family.

While I am able to move on with peace of mind, I am still imprisoned by this virus. Every time I get a cough or feel something in my throat, I worry.

Even if I am safe physically from it, many are not. People are still falling ill and still dying from it with seemingly no end in the near future.

Yet, there are reasons to be optimistic. Testing for COVID-19 has increased across the country and so are the numbers of people recovering after getting the virus. Even more encouraging are the antibody tests that are starting to pop up.

“I think the American public have done a really terrific job of just buckling down and doing those physical separation and adhering to those guidelines,” Fauci told NBC News. “But having said that, we better be careful that we don’t say, ‘OK, we’re doing so well we could pull back.’ We still have to put our foot on the accelerator when it comes to the mitigation and the physical separation.”

Michael Kinney Media

Congratulations Michael. So glad you are over this hurdle. The Stoneman family is praying for you. Great article you wrote.